Investing in the tool (Transactional) or the teacher (transformational)?

This Insight examines why curriculum alone rarely improves math outcomes and shows how investing in teachers mathematical knowledge is one of the most cost-effective ways to strengthen instruction

Introduction:

If districts continue investing in curriculum and PD, why aren’t math outcomes improving?

Classroom instruction in mathematics requires teachers to make hundreds of decisions each day about representations, questions, pacing, and how to respond to student thinking—often within the constraints of new materials and limited instructional support. Research consistently shows that we have overestimated what curriculum alone can accomplish and underestimated the power of teachers’ mathematical knowledge for teaching (MKT) (Ball, Thames, & Phelps, 2008; Hill, Rowan, & Ball, 2005). This overview examines how districts allocate funds, what the research says about the relative impact of curriculum versus professional learning, and why shifting even a small percentage of existing budgets toward content-focused math PD is one of the most cost-effective strategies available.

How Districts Spend: Curriculum vs. Professional Development

Where does the math dollar actually go—and how much reaches teacher learning?

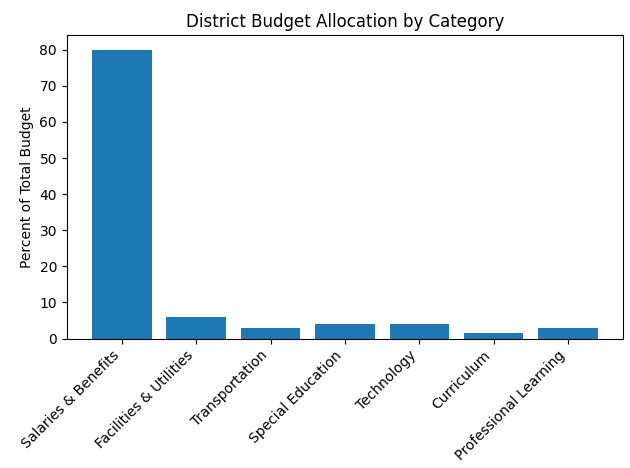

Most districts spend 80-85% of their overall budgets on salaries and benefits, leaving just 15-20% for transportation, utilities, technology, curriculum, assessments, and professional learning (Education Resource Strategies, 2020). Within that discretionary portion, curriculum and PD together account for only 3 to 6% of total spending (Center for American Progress, 2018). When annualized over adoption cycles, math curriculum often represents just $7-$25 per student per year, while math-specific PD averages $20-$60 per student (Learning Policy Institute, 2017).

This means that math teaching—one of the strongest predictors of long-term student success typically receives less than 1% of total district resources, and only a fraction of that PD focuses on building teachers’ deep mathematical understanding. To put this in perspective: For every $100 a district spends, the entire engine of math improvement both the tools and the training to use them amounts to little more than loose change found in the couch cushions. It is no surprise this level of investment fails to produce transformative results.

Figure 1. Typical allocation of a $100 million district budget. After fixed costs, only a small portion remains for curriculum and professional learning combined.

Why Curriculum Alone Rarely Delivers Meaningful Gains

If curriculum is improving, why isn’t student learning improving with it?

High-quality materials matter, but decades of research demonstrate that the impact of curriculum is mediated by teacher knowledge and instructional practice (Cohen & Hill, 2001; National Research Council, 2001). Teachers who lack strong content and pedagogical content knowledge often reduce rich tasks to procedural routines, limiting opportunities for reasoning (Ball et al., 2008). When outcomes fail to improve, districts often initiate another expensive adoption cycle a response that masks the underlying challenge: insufficient investment in teacher knowledge and instructional capacity (TNTP, 2015).

Publisher-led trainings, while helpful for orientation, are rarely designed to build a deep understanding of mathematics or learning trajectories, and short-term workshops rarely produce lasting instructional change (Garet et al., 2001; Yoon et al., 2007). The result is a system that repeatedly changes materials rather than addressing the conditions required for strong implementation.

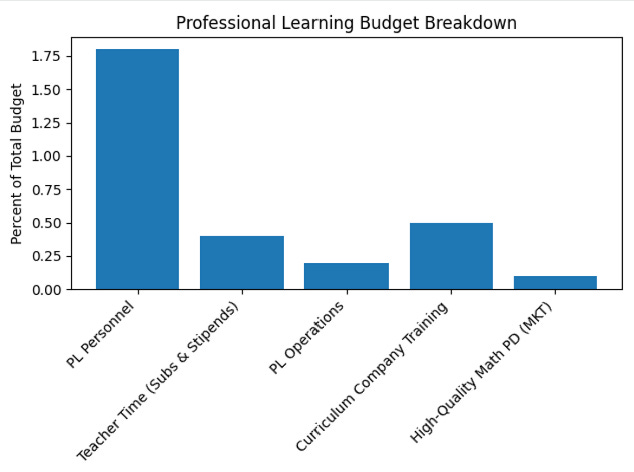

Figure 2. Breakdown of professional learning spending within a typical district. Only a small fraction supports sustained, content-focused mathematics professional development.

The Multiplier Effect: Why Math-Specific PD Improves Learning More Than Curriculum Purchases

What changes when districts invest in teachers’ mathematical knowledge instead of relying on materials to carry the load?

A large body of research shows that teachers’ expertise is the most influential in-school factor affecting student achievement (Hattie, 2009). In mathematics specifically, teachers with stronger MKT produce significantly larger learning gains, even with the same curriculum (Hill et al., 2005). Unlike curriculum, which expires every 6-8 years, teacher knowledge is a durable, compounding asset.

High-quality PD helps teachers understand why mathematical ideas develop the way they do, how representations support thinking, and how to respond to student misconceptions. This means a teacher can instantly recognize why a student is consistently adding denominators when adding fractions a misconception that the curriculum script may not address and can use a visual model to rebuild understanding in the moment. This is the difference between covering material and teaching children. Sustained, content-focused PD — rather than isolated workshops has been shown to improve instructional practice and student outcomes meaningfully (Desimone, 2009; Garet et al., 2001; Yoon et al., 2007).

Rebalancing the Investment: Spending the Same Dollars More Strategically

How can districts use existing funds more effectively to improve math learning?

Districts do not need new money to improve mathematics outcomes; they need a smarter allocation of the funds they already spend. The shift required is not from low spending to high spending, but from a transactional investment in materials to a transformational investment in teacher expertise. In many districts, annual spending on professional learning alone exceeds $1 million, yet only a small portion of that investment is directed toward deepening teachers’ mathematical knowledge for teaching (Education Resource Strategies, 2020).

A Strategic Reallocation: A $1 Million Thought Experiment

Consider a district that spends approximately $1 million per year on professional learning across all subjects. Even a modest reallocation within this existing budget can have outsized effects. For example, redirecting just $100,000–$200,000—10–20% of the professional learning budget—toward sustained, content-focused math professional learning can double or triple the district’s current investment in teacher mathematical knowledge without increasing overall expenditures.

This shift is not about cutting support, but about targeting resources more effectively. Districts can make this reallocation by selecting high-quality but less expensive instructional materials, reducing reliance on low-impact, one-day workshops, and integrating curriculum implementation with ongoing math-specific professional learning. When curriculum and professional learning are treated as a unified strategy rather than separate line items districts build internal instructional capacity that strengthens the impact of any curriculum, present or future.

Equity and Long-Term Impact

How does investing in teacher knowledge advance equity in mathematics?

Students in historically marginalized communities are more likely to be taught by novice teachers and less likely to receive instruction grounded in strong mathematical understanding (von Hippel et al., 2018). When new materials are distributed without corresponding investment in teacher learning, implementation gaps widen, and students who most need conceptual instruction receive the least.

By prioritizing deep, sustained math PD—especially in high-need schools districts can improve consistency, reduce remediation needs, and create more equitable access to meaningful mathematics. This is how investment in teacher knowledge becomes an act of educational justice.

Conclusion:

If curriculum is the map, teacher knowledge is the driver. Because math curriculum and math-specific PD together account for well under 2% of a typical district’s budget, even small strategic shifts can produce substantial gains in instruction and achievement. Real, lasting improvement will not come from the next adoption cycle; it will come from sustained investment in teachers’ mathematical knowledge for teaching—the most important and enduring asset in the system.

Here’s an additional document to provide more insight on the topic:

References

Ball, D. L., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407.

Center for American Progress. (2018). Lessons from school districts on curriculum spending.

Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2014). Learning and teaching early math: The learning trajectories approach (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Cohen, D. K., & Hill, H. (2001). Learning policy: When state education reform works. Yale University Press.

Desimone, L. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199.

Education Resource Strategies. (2020). Resource use in schools: A systems perspective.

Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., & Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes PD effective? American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 915–945.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Hill, H. C., Rowan, B., & Ball, D. L. (2005). Effects of teachers’ mathematical knowledge for teaching on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 371–406.

Learning Policy Institute. (2017). Effective teacher professional development.

National Research Council. (2001). Adding it up: Helping children learn mathematics. National Academies Press.

TNTP. (2015). The mirage: Confronting the truth about teacher development.

von Hippel, P. T., Workman, J., & Downey, D. (2018). Inequality in teachers’ access to professional development. AERA Open, 4(3), 1–20.

Yoon, K. S., Duncan, T. S., Lee, S. W.-Y., Scarloss, B., & Shapley, K. (2007). Reviewing the evidence on how teacher PD affects student achievement. Institute of Education Sciences.